Location: Ex-Cavallerizza, Piazzale Giuseppe Verdi

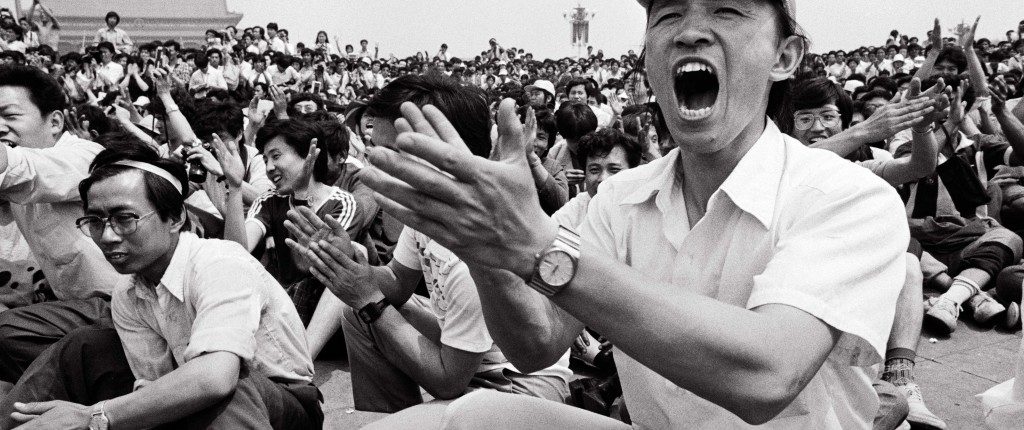

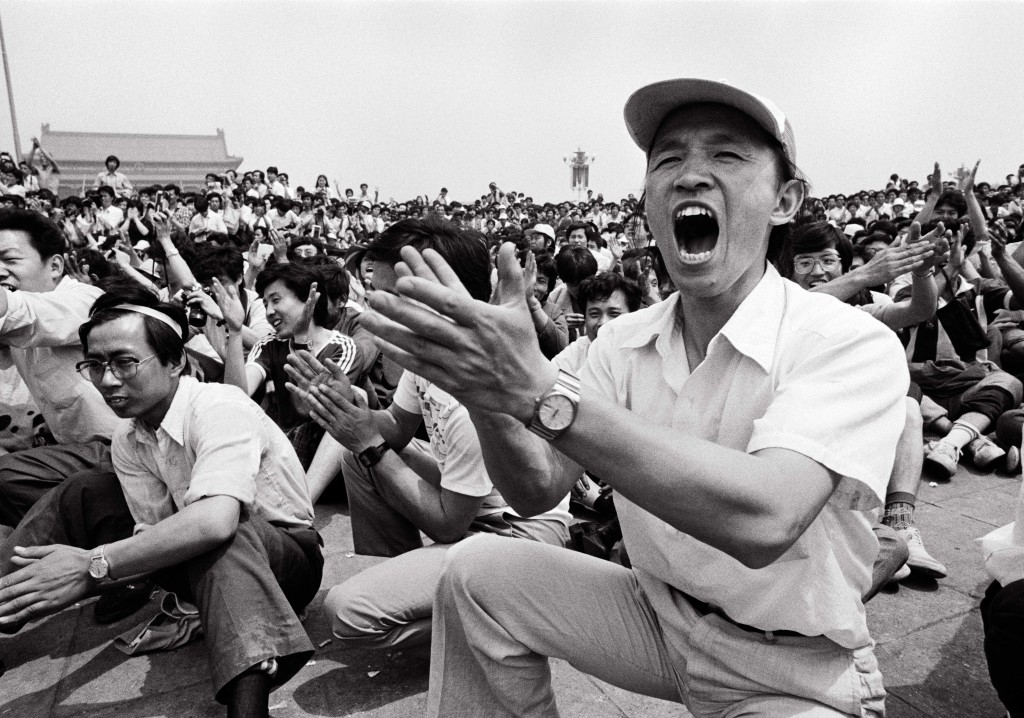

THE LONGEST NIGHT —DARIO MITIDIERI

curated by Renata Ferri

On May 24, 1989, Dario Mitidieri, a thirty-year-old Italian photographer living in London, leaves the city on a British Airways flight headed to Beijing. The Sunday Telegraph, his employer at the time, paid for the airline ticket. He has allowed himself ten days to complete a report on the students who have occupied the city square for over two months. The square is that of Tiananmen, symbol of the communist power of China. The flight back to London is scheduled for June 4th. He has loaded his camera with Kodak Tri-X black and white film and has started working. The protest is in its most critical phase: the students have declared a general strike of the university and the demonstrations follow one another. A few days before, on May 13, about two thousand students have occupied the square and some of them have started a hunger strike.

As the days pass, intellectuals, workers and citizens join them. The protest spreads out from the capital, reaching hundreds of cities. Attempts at mediation and dialogue with the government do not solve the situation, martial law is proclaimed but the protest does not stop. In a crescendo of tension, on the night of June 3rd the Army moves from the suburbs to the city centre, directed to Tiananmen.

Dario Mitidieri, like others, does not immediately realize what is going on. All of a sudden it happens, it’s 8 in the evening, he’s having dinner at the Beijing Hotel when he hears the shots. At that precise moment, his longest night begins.

In the bustle of the crowd, the tension is now skyrocketing, sirens and screams pierce the darkness. The chaos lasts many hours. As Mitidieri recounts: “The most dramatic moment I experienced in Tiananmen Square was the early morning of June 4th when some doctors, taking huge risks, sneaked me into the hospital where they were working, the Tiananmen Square Hospital, the closest one to the square. There I realized what had happened there, I saw the wounded and the dead in the rooms and corridors of the hospital. There, with trembling hands, I documented everything I could: the casualties and the bodies piled up in a room. A doctor told me: “Take photographs and show the world what the Chinese army is doing”. So I did. It was one in a lifetime experience for a photojournalist: one of those rare cases in which the images do not only serve to tell a story, but testify the truth that the Chinese government was trying to divert and suppress”.

Those photographs were among the first to arrive in the West, they were published on all the front pages of English newspapers, then on the magazines: The Independent Magazine, Stern, l’Espresso, l’Europeo, and many others.

They did not have the echo or the power of “Unknown Rebel”, the iconic image of the young man standing perfectly still in the square, stopping the tanks, with a small but significant gesture, as they move towards him, the same tanks that, over the following hours, would crush the student protest in blood.

That photograph and its different versions, taken by some great photographers, such as Stuart Franklin of Magnum, Jeff Widener of the Associated Press and Charlie Cole of Newsweek, went around the world. An icon was born, so much so that, in 1998, Time included the “Unknown rebel” in the list of “people that most influenced the 20th century” and in 2003 Life included it among the “100 photos that changed the world”.

The history of Tiananmen is still full of dark sides and hasty reconstructions but, within history, that photograph has been a story in itself. Like all icons, it does not tell what happened before and after and what was happening around. It contains the immortality of the moment and is exhausted into it. In its power of synthesis it leaves no room for speculation, it does not allow shadows and shows no folds in which to look for meaning, to ask questions, to be assailed by doubts. Such task belongs to narrative photography, which is able to investigate, sometimes to anticipate the events and is, always and in any case, attentive to the unfolding of situations and their evolution, following the parabola of history, contemplating every significant nuance.

After so many years, we still know very little of what happened, there has never been an official number of victims of that night and of the executions that followed to suppress the revolt and dissent. What the Chinese government called a Tiananmen Square incident, in democratic history is known as the Chinese Democratic Spring or simply the Tiananmen Square uprising.

An event that, due to circumstances and timing, had an enormous influence on what unfolded in that incredible year, 1989 – a few months later the Berlin Wall would fall – and that changed the course of history forever.

This is why today, thirty years after that tragedy, the work of Dario Mitidieri takes on new importance. It allows us to return to those days through vivid images, marked by dramatic moments. Extraordinarily imperfect, like juxtaposed written notes, frantic jottings to capture history, the set of these fragments becomes a story, a chronicle and a testimony: by looking at them, one can almost hear the sounds and the cries, can notice the broken movements, the astonished looks as the merciless night witnesses the tragedy.

Among Mitideri’s images, all full of symbolism, one stands out: the photo of the child who seems to be giving his “welcome” to the soldiers. Taken a few hours before the start of the massacre, it expresses very effectively the innocent state of mind with which the thousands of protesters had, until then, waited for a response from the authorities.

Photographic narration offers new emotions in the face of those facts, which is why it allows us to reflect much more deeply, not only on what happened, but on the meaning of those events.

Here, then, comes the past flowing through the images, giving back a single representation, in which ghosts and fears change appearance and places, making it extremely contemporary. These ghosts, appallingly present, can be clearly recognized in any regime that violates human rights, does not contemplate dissent and denies freedom.

© Romano Cagnoni

© Romano Cagnoni